Can the shem be removed from the mouth of the golem?

Thoughts on creation, its immortal consequences, and the unmaking.

Dear Reader,

Since I started reading Frankenstein, I have been obsessed with stories about humans creating life in unnatural ways. That is when I stumbled upon The Golem of Prague. If you are unfamiliar with the myth, I have included a short summary below.

The Golem of Prague comes from Jewish folklore, most often tied to Rabbi Judah Loew ben Bezalel in the late 16th century. To protect the Jewish community of Prague, the rabbi creates a humanoid figure from clay and brings it to life using sacred language. In some versionss, a word is inscribed on the Golem’s forehead; in others, a shem, a “sacred name” is placed inside its mouth. The Golem is obedient and literal-minded. But over time, it grows violent or continues working when it should rest. To deactivate it, the rabbi must remove the shem from its mouth or alter the sacred word. Once this is done, the Golem collapses back into clay. In many stories, its remains are stored in the attic of the Old New Synagogue.

The Shem, Life-Giving Word

When I learned about this folklore, it instantly reminded me of the laws of nature. Once creation is unleashed, there is a possibility that it could exceed its creator’s intentions. The correlation between the rabbi and nature that we can observe is this: creation is not a failure, but the important realization is when it must be unmade. Look at the systems around us, some of them execute commands so perfectly without understanding why. When we take shem as the meaning of creation itself, that is when it all makes sense.

What caught my attention is not the legend or the story, because the same concept has been existing in many cultures. But the removal of shem! That is interesting. It is as close to soul or meaning as I can define it. In the story, the name of God, when inserted, brings the golem into being, and when removed, returns it back to matter. Of all the cultures, history, fiction, and science, I do not think creation is rarely our problem. Where we have to pay more attention is in realizing and deciding when we must pull the plug. And especially when doing it, those involved must still know what the act means.

Our Modern Golem

A friend of mine has recently shared this amazing course → Mimbres: Ghost in the machine, which is about our obsession with godlike power, from medieval warfare to the atomic bomb, which examines how technological progress is repeatedly outrunning ethical control. Following that thread, I fell into the rabbit hole and stumbled on this research article by Sebastian Musch → Hans Jonas, Günther Anders, and the Atomic Priesthood: An Exploration into Ethics, Religion and Technology in the Nuclear Age. The article was very interesting and it did trigger a few thoughts which I would like to talk about. I have treated Musch’s paper as intellectual framework in writing this essay, and not summarizing it. For the full account, the original article is well worth reading.

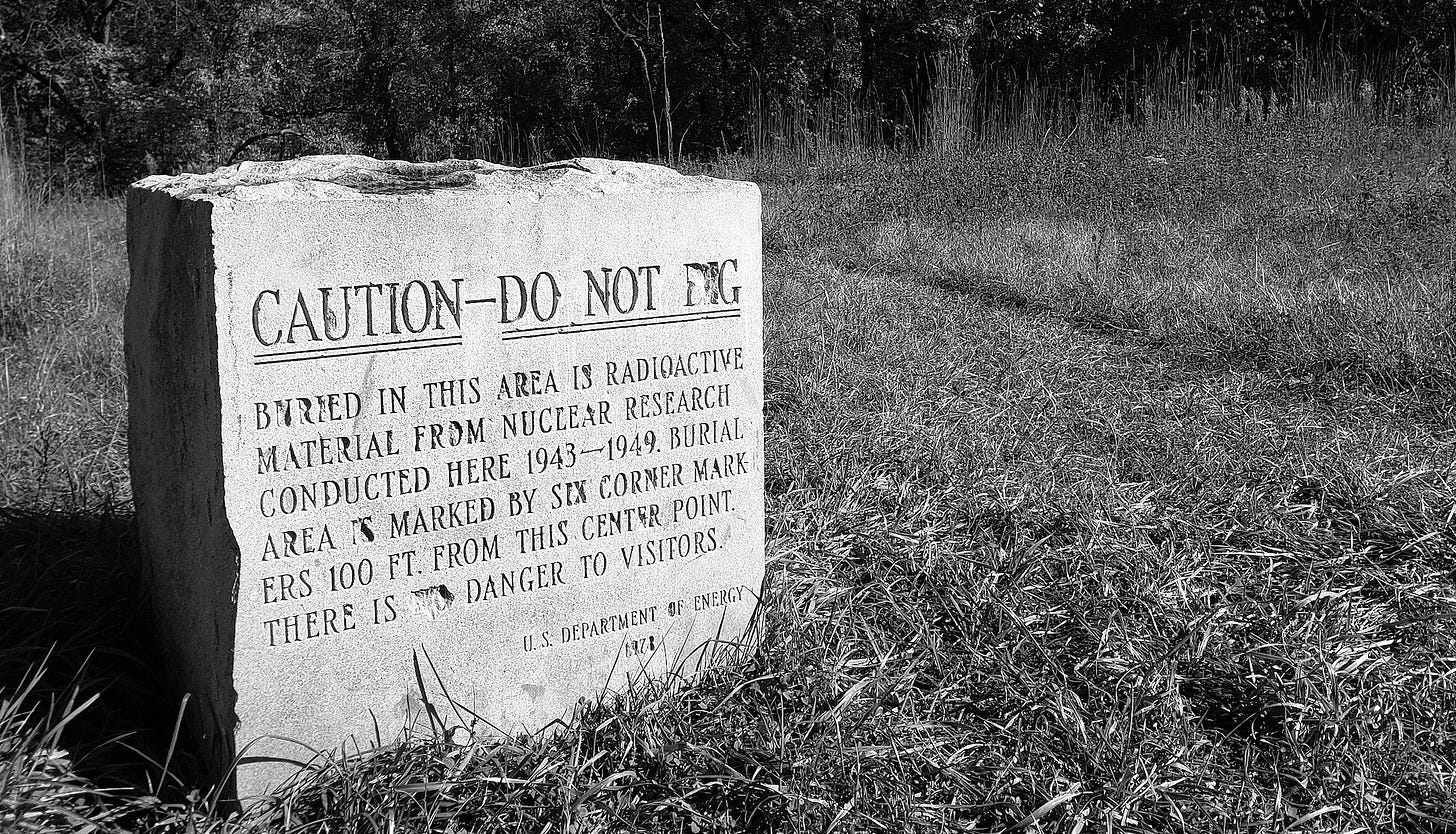

Now think about nuclear technology as our golem and nuclear waste as its afterlife. If considering a golem that big of a nature, for argument’s sake, let’s take an example of the powerful technology which is harmful for our race. And how I understood Atomic Priesthood → Long-term nuclear waste warning messages, is our desperate attempt to make sure that the shem is never touched by the wrong hands or never touched at all. I would like to believe (though I cannot fully), that the creation of this golem and its animation is to protect the community, not to destroy its own. But over time like always, the golem grows strong and becomes autonomous. Most of the creation begins with a purpose of protection, or progress, or even efficiency sometimes, but again we see it taking sideways and ending in excess or unintended consequence.

Ati sarvatra varjayeth, (अति सर्वत्र वर्जयेत्) is a Sanskrit phrase meaning “excess of anything is bad” or “excess should be avoided in all things”

Immortal Consequences

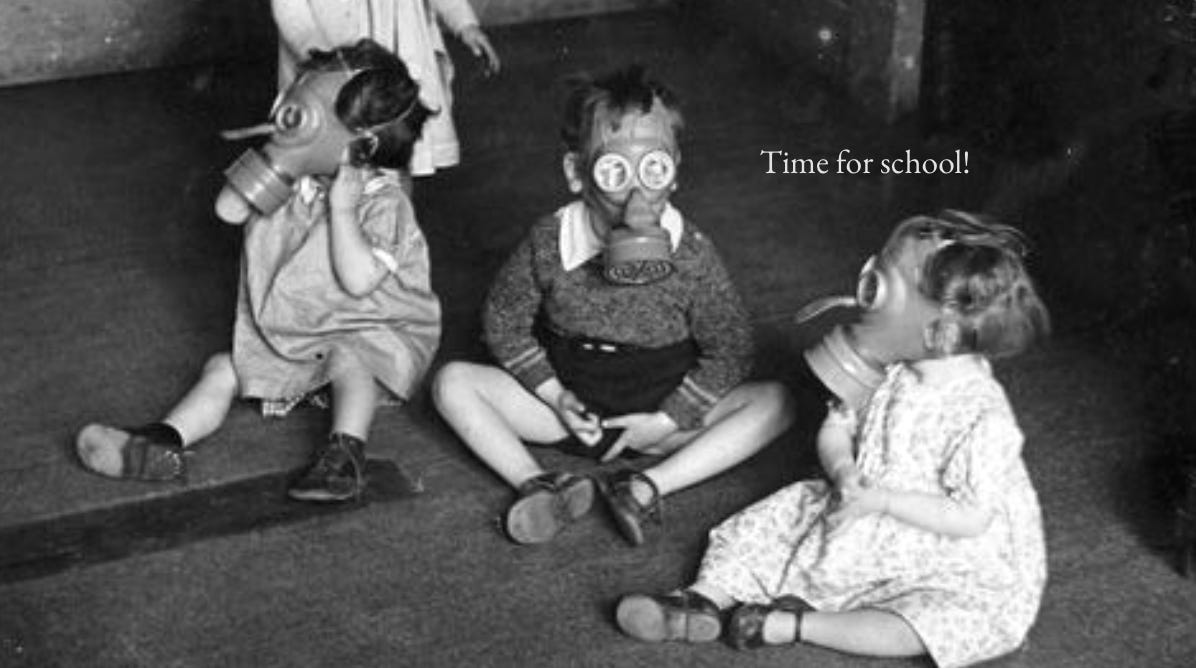

When we go back in time and look at our history, the action and consequence of many disastrous events had a visible arc. We could see what our tools did, and we outlived those mistakes. But we humans are creatures of habit. The coming generations make the same mistake in a different form, and the cycle continues. But with nuclear technology, this cycle is broken. A decision made in one generation radiates its harms across thousands of years. The problem is not stopping this golem, because it does not stop walking even when its creator has died.

We hear a lot about ethics, morals, and why they are so important in the current age. But do we truly understand what these words demand of us? I don’t think we ever will, until we stop gambling with the futures we cannot imagine. We treat the bad consequences (long-term harm) and uncertainty as some problems that needs to be solved later, leaving it to future generations (who by the way did not choose them), because it is not our current problem. All we do is cash in our current profitable consequences. When our unsolved problems come back to bite us, then we start initiatives and programs to fix them, but most often it is too late.

One simple example is global warming and climate change. Most of us (including myself) make decisions which are easy for our current way of living, that might have terrible effects for future generations, but we still do it. Because we like the immediate comfort and profit it offers presently. And we believe that whatever progress humanity is making, the progress will clean up after itself in and for the future.

The Atomic Priesthood

The atomic priesthood that is discussed in the article comes to life precisely at this point where all these prohibitions become unbearable. When technology exceeds our ethical vocabulary, we begin to borrow from religion. This essay that I am writing now is an example of it. I cannot put to words the damage all the powerful and advanced technology is causing our habitat, resources, and future generations. And here I am, seeking the concept and language from myths to express it.

Atomic priesthood is a concept for a future religious-scientific order tasked with guarding knowledge of dangerous nuclear waste sites for millennia, long after our current civilization collapses. To simplify it, how do we warn future civilizations about dangers they cannot see, in languages they do not speak, using symbols and myths they may not recognize? Because nuclear waste will remain lethal long after our political systems, scientific institutions, and current social systems have long gone.

These questions are not just speculative, because they are already embedded in the earth. One of the examples is Onkalo, Finland’s deep geological repository for spent nuclear fuel. It is carved into ancient bedrock and designed to remain sealed for roughly 100,000 years. It is intended to outlast languages, nations, and maybe any recognizable forms of social life. What is interesting is, the site is consciously left unmarked once it is closed. Because any warning might invite curiosity, and curiosity might lead to excavation, and then, excavation might awaken what was meant to sleep.

Myths and Warnings

One of the reasons I believe religions survived this long is because myths survive when our manuals or instructions fail. And the core of myth is, fear, which I think travels farther than information. And the concept of atomic priesthood is designed on this very thing. Certain places must become unapproachable, and to stay that way, they need to be feared. Myths are told and continued because they are not understood, and we take a myth as a myth, and the fear it brings in. So the future generations need not understand why certain places are unapproachable; they just have to be feared. That means it requires future humans must be lied to for their own good.

This brings me back to my previous point on how we compensate when it’s too late. We build another system or control mechanism when something has gone beyond our hands to control. That is where the shem comes into the picture. It becomes our responsibility to remove the shem, but mind you, this is not something we do out of ethical responsibility. We do it because it is necessary for survival. With all the advanced and powerful technology, let it be AI or nuclear, can the shem be removed from the mouth of the golem? Or is it too late? Have we passed the point where the removal could be possible? Which is leaving us with only rituals or stories of warning, because atomic priesthood, to me, seems to be one.

Can the Shem Be Removed?

It reminds me of the scene in the Oppenheimer movie when he realizes, what have we created?! That admission! To admit that we created something we cannot fully undo. The question, then, is not only whether the shem can be removed. It is whether we will still recognize it when the moment comes?

I think creation itself is not the crime, because it never has been. The impulse to create is what made us curious, take for example tool making or storytelling. Without these, there would be no civilization, no science, no art, no language in which to even pose these questions. Expecting humanity to stop creating is neither realistic nor honest. The Golems always exist because we cannot resist giving life to what we want to explore. Then, the ethical burden is in knowing when a creation has gone beyond its purpose and has lost its meaning. Nuclear waste buried deep, and intelligent systems that learn beyond their designer present us the same ancient Golem problem in different forms.

So, will there be anyone left who remembers that the shem was placed there by human hands, and that it can, in principle, be removed by them as well?

Yours in thought,

Yana