Running towards what we flee

#1 — The Greek Dispatches: Oedipus Rex by Sophocles

Slowly reading Greek literature, tragedies, and mythology as a long, lived thing by staying inside the events until they start giving me meaning.

An essay about fate, free will, certainty, and prophecies in Oedipus Rex, a Greek tragedy by Sophocles.

I haven’t explored Greek literature much, and this tragedy play seemed like a good place to start. Written between 430 and 426 BCE, it offers a window into the morals, principles, and values of that time; essential for understanding how humanity thought and lived, which is what my Reading Project is all about.

Of Sophocles’s 120 plays, only 7 have survived. Oedipus Rex is regarded not only as his finest work but also as the purest and most powerful expression of Greek tragic drama. Now that I’ve read it, I can see why!

The tale runs on the theme of tragedy of fate. But I see it as a tragedy of certainty and the dangers that come with being too sure. Our need to know or anticipate the future (which, by the way, is the primary cause of anxiety), I think, stems from a fear of life’s unpredictability.

For Those Who Haven’t Read It

Note: If you’ve already read the play or know the story, feel free to skip this section and continue to the essay.

Oedipus Rex tells the story of Oedipus, the king of Thebes, who tries to flee from his fate but inevitably meets it in the end. The city of Thebes suffers a plague, and Oedipus seeks to stop it. The Oracle at Delphi reveals that the plague will end when the murderer of the previous king, Laius, is found and punished. Oedipus vows to find this killer, unaware that he himself is that very man.

Years earlier, a prophecy foretold that Oedipus would kill his father and marry his mother. Believing his parents to be the king and queen of Corinth, Oedipus had fled their kingdom to avoid this fate. However, in a tragic twist, he had already unknowingly killed Laius (his true father) at a crossroads and married Jocasta (his true mother), the widowed queen of Thebes. Oedipus and Jocasta have two sons and two daughters from their marriage.

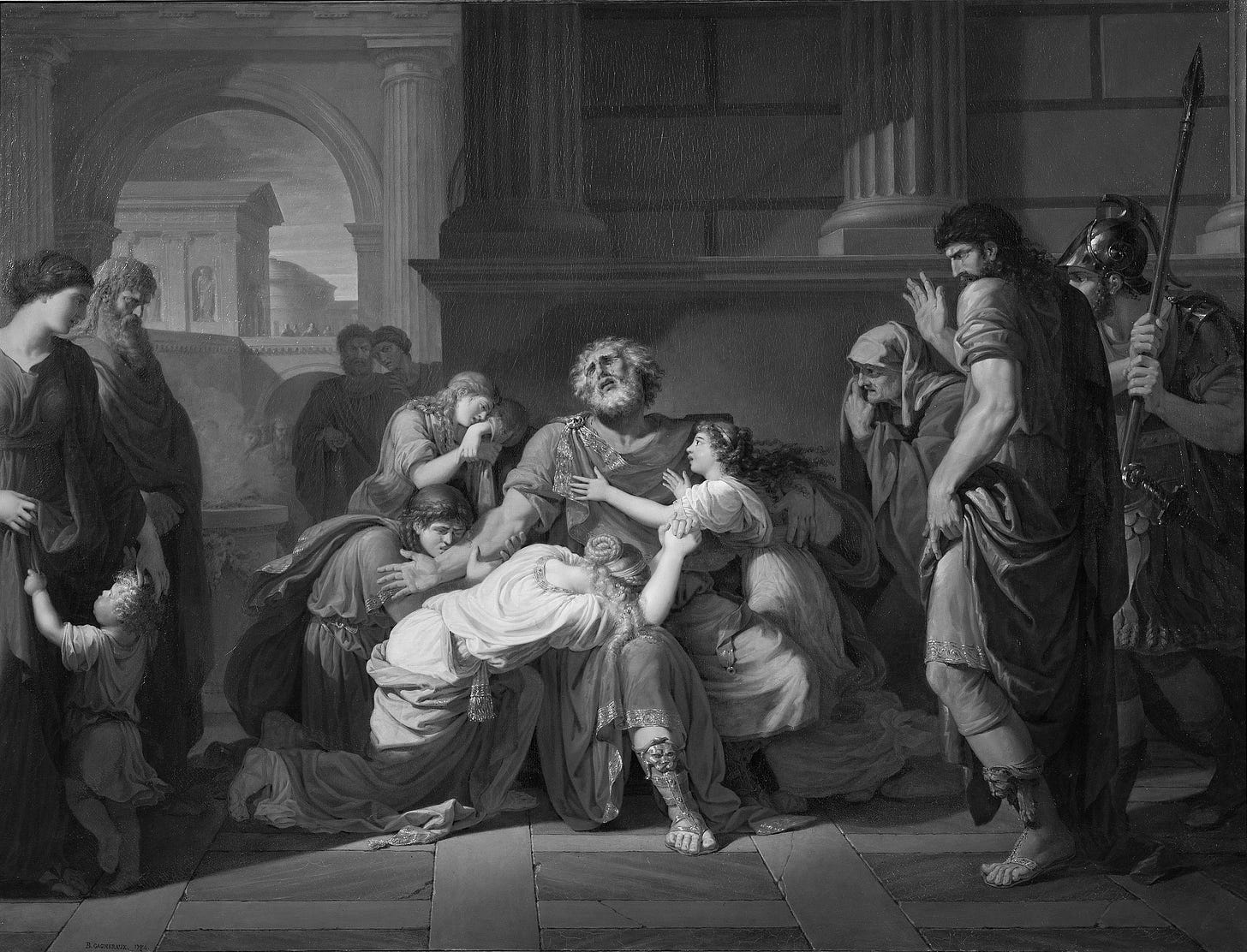

As the truth emerges through interrogation and various witnesses, Jocasta hangs herself, and Oedipus blinds himself with her gold brooches. The play ends with Oedipus, now broken and blind, accepting his terrible fate. That, is the tragedy.

Fate vs. Free Will

Who is responsible for the fall of Oedipus? Fate or himself? This question has haunted me since finishing the play. On one hand, the prophecy seems inescapable, as if divine powers predetermined Oedipus’s tragic end. On the other hand, his own actions, his temperament, and choices drove the story forward.

Greek literature is deeply rooted in the belief of fate and the power of gods. I sometimes think such deeply held beliefs resist rational explanation. Time and again throughout the play, we see that humans cannot overcome their destiny. If we believe in fate, then we are fated to a life beyond our control. Yet I’m awed by how the characters’ attempts to escape their fate are precisely what fulfill the prophecy.

Laius and Jocasta tried to change their destiny because they knew of it. They thought they had cheated Apollo of his will by attempting to kill their infant son. Similarly, Oedipus knew the prophecy but believed his adoptive kingdom of Corinth and its rulers to be his parents. He fled, thinking he would escape the prophecy.

But the actions in the story are purely Oedipus’s own — his uncontrollable temper, his arrogance, especially his rage. If he had kept a cool head, he wouldn’t have killed Laius at all.

As I read, I kept thinking: what is meant to find you, will always find its way to you, no matter how hard you try to alter the course.

When emotions rule us, that is when the doom of morality begins. I read about the American theologian Tryon Edwards’s words on human destiny:

“What could contribute to the making of one’s destiny? Thoughts often lead to purposes; purposes go forth in actions; actions form habits; habits decide character, and character fixes our destiny.”

Tragedy of certainty

Apart from the certainty in prophecies, there’s another certainty that’s clearly evident in the tale: Oedipus’s certainty about himself. He was so sure, so convinced he had done everything to avoid the prophecy. There’s an egoistic arrogance in his belief: “I, Oedipus, can do no wrong.” Yet he is also a man of honor. He calls himself the man “abhorred of gods, accursed of men.” At the end of the play, he even blinds himself as punishment for sins he committed, though unintentionally.

This certainty, this belief in one’s understanding, is what I think truly led to his downfall. Creon (the king’s brother-in-law and uncle) says it as well:

“the man who thinks that bitter pride alone can guide him, without thought — his mind is sick”

Before Tiresias (a priest in Thebes) accused him of being the murderer, Oedipus was respectful and believed in the priest. But as soon as the tides turned, he started protecting himself and blaming others. Where was his respect for morals then? He even mocked Tiresias as “this magic-man and schemer, this false beggar-priest, whose eye is bright for gold and blind for prophecy.”

These are the words of wrath.

When emotion takes over, it blinds us to our own deeds. The ability to feel and experience is the very essence of life, and also the cause of our doom.

Prophecy

There was so much prominence given to oracles at that time. I wonder what the equivalent is in our current era. Perhaps it’s our reliance on data, algorithms, expert predictions, or fake social media? Prophecies are often cryptic and lead us down a different path than we expect. Is this intentional? Or are we limited by our own understanding and judgment, biased toward outcomes we favor?

What I understood from the play is this: prophecies aren’t just predictions, but they’re images of our fears and desires. Oedipus didn’t run away from his fate, but towards it. In doing so, he embraced it. The same is true for Laius and Jocasta. Their attempt to kill their child was born of fear of what might come. Yet this very act set everything in motion.

I was particularly captivated by Tiresias’s words: “A fearful thing is knowledge.” Indeed, it’s not just that knowledge can be dangerous. It’s that incomplete knowledge, or knowledge without wisdom, can be catastrophic. Oedipus knew the prophecy but lacked the wisdom to understand that running from it was pointless.

Afterthoughts

I’ve always been drawn to the idea that we create our own fate through our choices. Yet Oedipus Rex complicates this. Even as Oedipus made his choices, to leave Corinth, to kill a stranger at a crossroads, to marry a widowed queen — fate was working through him. I’d like to think his choices were free, but they were also predetermined to end at a single point.

“Mann Tracht, Un Gott Lacht“ is an old Yiddish adage meaning “Man Plans, and God Laughs.“

If I had to summarize this read, it’s the play’s exploration of how small we are as humans when confronted with mysterious higher powers we can neither see nor understand. Should we accept our fate passively, making no attempt to resist? Or should we struggle against it, knowing we cannot win — fighting not for victory, but for dignity in inevitable defeat?

I’m left wondering:

If Oedipus had accepted the prophecy rather than running from it, could he have transformed his fate into something less tragic?

What I’m Reading Next

Yours in thought,

Yana

I’ve always loved this play. This is just so tragic, the way Oedipus tries to escape his fate only to meet it. I love your analysis when you say: prophecies aren’t just predictions, but they’re images of our fears and desires. Oedipus didn’t run towards his fate, but away from it. In doing so, he embraced it. The same is true for Laius and Jocasta. Their attempt to kill their child was born of fear of what might come. Yet this very act set everything in motion.