The Canterbury Tales: General Prologue, by Geoffrey Chaucer

The great poet is not just teaching me how to read poetry, but to read people.

Dear Reader,

What have I gotten myself into?

When I picked up Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, I thought I was signing up for a charming and witty medieval road trip. Maybe some good banter, a few fun tales, maybe a knight or two. But no. Just the General Prologue alone has more layers than my entire school history textbook! And I haven’t even touched the actual tales yet.

Chaucer, the so-called father of English poetry, what a mind! I’m beginning to see how he saw literature as a means to reflect and interrogate social structures. He so cleverly wrote about the English men and women of the 14th century, not just as characters, but as a picture of the past for future times.

“Chaucer taught us how to read the English mind as it was first finding its voice”

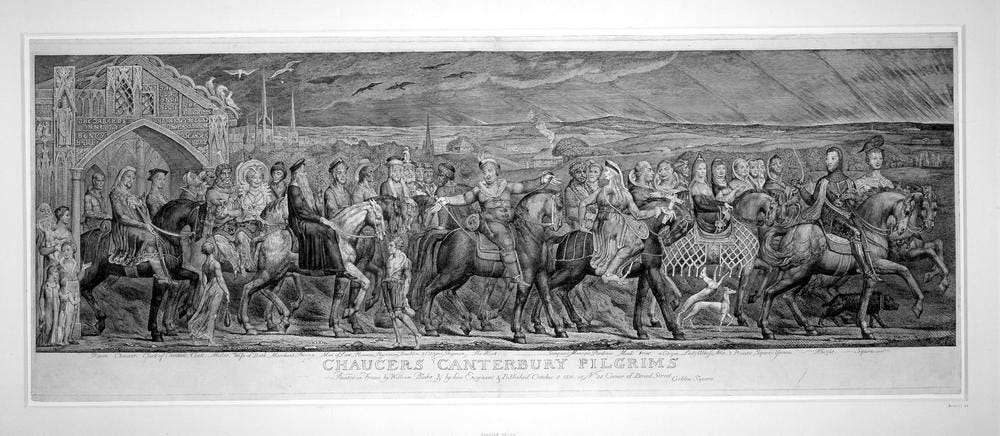

The Canterbury Tales is framed as the story of 30 pilgrims (29 travelers and a narrator) gathered at the Tabard Inn in Southwark, London, who set out on a 60-mile pilgrimage to Canterbury to visit the shrine of Thomas à Becket. Their host, Harry Bailey, proposes a tale-telling contest to pass the time. Each pilgrim is to tell two tales on the way there and two on the return, so that’s 120 tales in total. Chaucer only managed 24, and the pilgrims never actually reach Canterbury. The prize? A free supper, back at the inn, for the teller of the tale of “best sentence and most solaas”, meaning stories should be entertaining but also provide some moral instruction.

I must admit, I’ve fallen more in love with Chaucer’s staging than the storytelling. This pilgrimage isn’t just a structural setup for the book, but a societal one. The pilgrims are from every corner of the medieval world, belonging to different societal estates (I’ll talk about this in a few seconds). And, the characters are not named; they are purely identified by their role in society. So, clearly, the intent of the book is not about the characters but the estates or classes.

Chaucer arranges his cast according to the medieval “Three Estates”:

Those who pray (clergy)

Those who fight (nobility)

Those who work (peasantry)

In the ideal medieval world, these groups should function together for the good of society. Chaucer’s satire points out how the selfish and sinful directions of individuals threaten to break this down. The estate system is falling, and Chaucer is showing us why. Very brilliantly! (If I seem very excited, yes I am mind-blown)

Chaucer doesn’t tell you who they are. He shows you what they wear, what they carry, how they speak. He just describes them, and within those descriptions is all the hidden satire! No pilgrim is truly who they say they are or who they are meant to be based on societal expectations. And suddenly, you are not just reading, but you are investigating. Yes, it didn't feel like I was reading fiction, but solving some sort of an investigation of my own.

And then there’s the most interesting pilgrim of all: the narrator! He calls himself “Chaucer”, but we must not confuse the narrator with the author. In the general prologue, he introduces every character with admiration. But as I kept reading, I noticed something. The gaps. The irony. The author Chaucer, he knows what he is showing us, and it felt as if he wanted the reader to read against the narrator’s words. How brilliant is this?! That's where the satire is, between what’s said and what’s shown. And once you see it, you can’t unsee it.

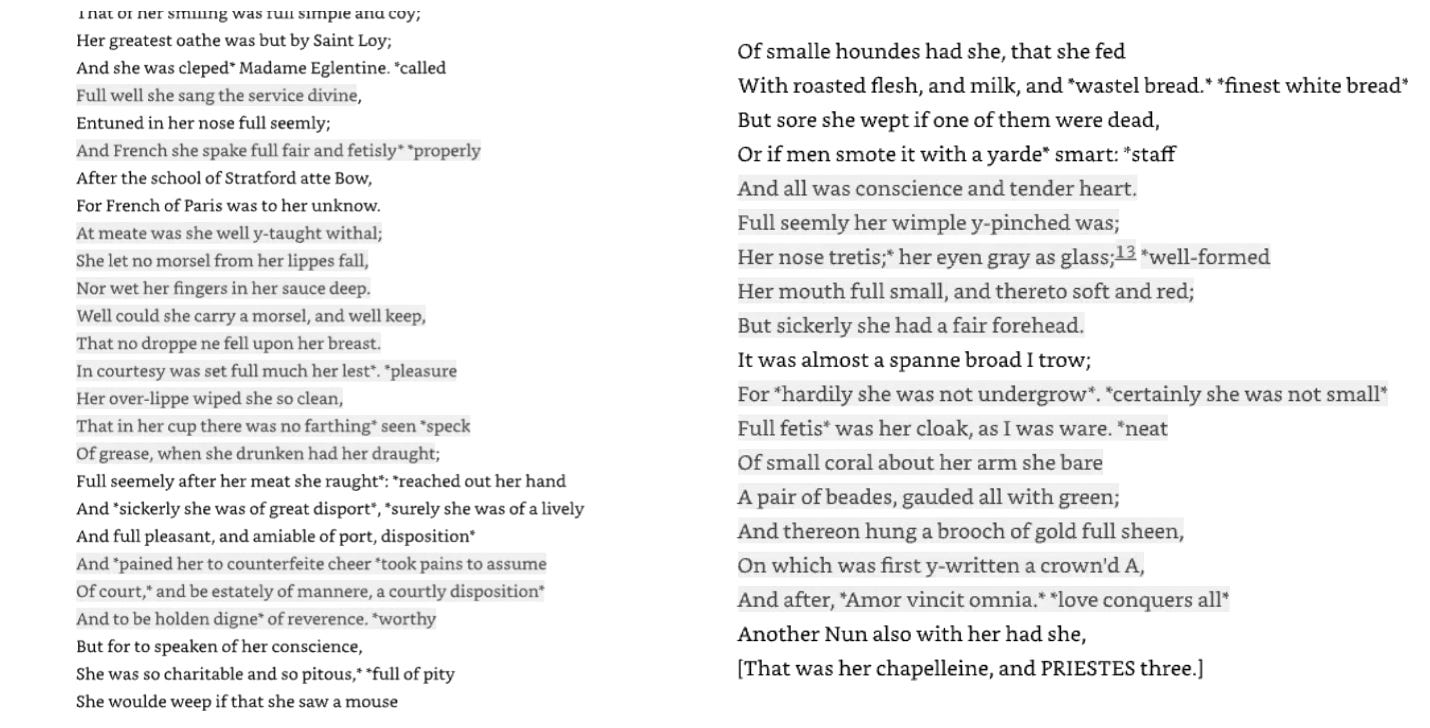

Take one of the pilgrims, the Prioress, also called Madame Eglantine, as an example. The narrator seems completely charmed by her and her gracefulness. He says she’s gentle, speaks softly, speaks French, and has exquisite table manners. He describes her more like a noble lady at a royal court than a nun in a religious order. But when you look more closely, we can see Chaucer’s hidden satire.

A prioress is supposed to be humble and focused on spiritual life and religion. So why is she wearing a shiny gold brooch that says “Amor vincit omnia” which means “Love conquers all”? That doesn't sound like divine or holy love, but sounds like courtly, even romantic love. And why does she cry more about a dead mouse than about poor people who are suffering (according to the estate and role, she’s supposed to be caring for the people)? Her expensive prayer beads, her stylish clothes, her focus on appearance and manners, all of it goes against what a nun should be, the role she’s supposed to play in society.

What Chaucer (the narrator) says: she is kind, pure, delicate, and noble.

What Chaucer (the author) shows us: she is performative, emotional towards worldly things, more concerned with how she looks than with what she believes.

He doesn’t point the finger. He hands you the evidence. That’s the clever part.

Chaucer isn’t just teaching me how to read poetry, but he is teaching me how to read people.

And now let me tell you about those opening lines.

WHEN that Aprilis, with his showers swoot*, *sweet

The drought of March hath pierced to the root,

And bathed every vein in such licour,

Of which virtue engender’d is the flower;- The Canterbury Tales, Geoffrey Chaucer

In the opening lines, Chaucer describes the sweetness of April showers, which we can translate to a celebration of spring’s return.

I’m seeing it more as a metaphor for celebration of renewal and rebirth; maybe even hope and direction. Where the soul, like the earth, begins again. Very beautiful introduction to the beginning of pilgrimage! A longing to remake themselves in the journey towards the sacred.

Now fast forward 5 centuries to T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, and we find a similar opening.

April is the cruelest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with spring rain.

Winter kept us warm, covering

Earth in forgetful snow, feeding

A little life with dried tubers.- The Waste Land, T.S. Eliot

But it is an opposite of Chaucer’s version of optimism. Chaucer is seeing renewal, and Eliot is seeing trauma.

When we think about the times Chaucer and Eliot wrote their works, Eliot’s time, the 20th century, he is speaking from a world filled with war, alienation, and even falling faith. I mean, this inversion of tone is not just a commentary but societal and cultural. Chaucer’s world still believed or had faith in pilgrimage, and Eliot’s questioned if the destination even existed. Wow! What a difference 500 years makes.

These little things are what make me fall in love with literature, every single day. Over and over again! Deeply! The way it holds both the past and the present. The way it lets us listen in on centuries of human longing, confusion, rage, faith, fear, and even doubt.

Until next time. I’ll keep reading, reflecting, and joining the pilgrims for their tales now.

Yours in thought,

Yana