Zeus really said “not my problem”

#3 — The Greek Dispatches: The war gets its first weapon, a golden apple

Slowly reading Greek literature, tragedies, and mythology as a long, lived thing by staying inside the events until they start giving me meaning.

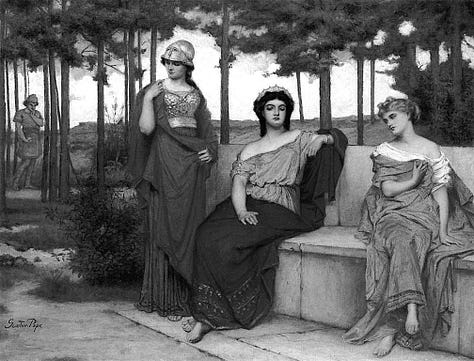

Backstory: At the wedding of Peleus and Thetis, parents of Achilles, Eris, goddess of discord, throws a golden apple into the room. It poses a simple, public question: who is the most beautiful? Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite cannot ignore it. A wedding party becomes a contest. Zeus opts out, pushing the responsibility of judgment into a mouth that isn’t his. The apple becomes the war’s first weapon.

Somehow, trouble and calm, both know the way to the human heart like veins and arteries.

I’ve just finished reading the backstory of the Trojan War, before I begin my slow reading of the Iliad’s main narrative. And I wonder, the first weapon in this huge war was a question that was carved into gold and left where everyone could see it: to the fairest. That seems like such a small thing to ignite a world, and yet it’s all it takes to change the temperature of a room. If the same question was asked in private, it would seem like flattery to make somebody smile. But the whole mess started when the question was posed and demanded as a public ranking. To give the title of the most beautiful will rearrange the whole dynamics of who is above and who is below. I think wars begin there, long before any ships have sailed and long before anybody bleeds: who’s above and who’s below. It’s the moment the war learns it can hurt someone without drawing blood.

Once the question barges into the wedding party, someone has to answer it or refuse it or even pretend it does not need answering. But none of these are neutral choices because if no one picks the apple, who is refusing it? The whole point of the apple is not about “the fairest,” but it was designed as a means to humiliation. The cleaner way to design it is to use beauty, because unfortunately beauty is a socially permitted reason to rank women without admitting you are ranking status.

When the public humiliation is between the goddesses, then it becomes a melodrama of its own kind. Myth survives with stories, and people telling those stories. And one such humiliation story is the story of the golden apple of discord. Being hurt in public with witnesses who will remember and retell what they saw. We pretend we live in a world of private feelings and personal choice, but so much of what we do is shaped by the fear of what will be said later or the story that will be told about us.

A humiliation that happens in private is still devastating, and it belongs to the two people (mostly) inside it. But public humiliation on the other hand, grows its own body to live, legs to spread, and a mouth to twist the facts. Someone humiliated is seen being hurt by witnesses who might not even mean harm. But it still travels and spreads because that grown mouth will retell this memory to others. I came across a talk by Ute Frevert (video below), and in her book she argues that shaming works as an instrument of power, not only when a state punishes, but also when institutions do, when ordinary groups do, and when the media does. It doesn’t mean people are bad, but that shame can be passed around. Even when formal punishment changes its shape, the social appetite for shaming can simply migrate into new places: schools, workplaces, newspapers, and the internet. It made me think of the apple again. You don’t need to hit someone to control them. Just place them under a light with other people watching.

I understand why it’s important for the three goddesses, Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite, to win the contest. For Hera, queen of Olympus, to be ranked second in a public forum would be to undermine her authority. Queens don’t lose contests in public and remain queens. Athena here is facing a different calculus altogether. She is the goddess of war and strategy; somebody who doesn’t/cannot lose. It’s no longer about being told you are not the fairest in public for her but about the challenge to status. As for Aphrodite, her reason is the most existential. As the goddess of desire and love, she exists in the realm of attraction and longing. One can imagine all the bodies and faces turning towards her in the hall when the apple’s inscription was revealed. If she loses a beauty contest, the very category that defines her essence, what is she then? What remains of her divine identity?

When the three goddesses go to Mount Ida with Hermes to visit Paris, that moment, the problem leaves the room and begins looking for somewhere else, more precisely, somebody else’s (not Zeus) throat to live in. When the goddesses meet Paris (Alexander), that’s when the apple finds a carrier. The problem has found a carrier. I reckon his first instinct should be to run. His second, to freeze. Or ironically, the third, to pray. Then the mind catches up and asks the most useless question in the world. Who do you pray to when gods are already standing in front of you? The moment the apple changes its owners, that’s when Strife succeeded in her plan. The golden apple made gods into a conflict, and now it needs to become a conflict that can spread.

The story becomes more interesting when the most powerful figure in the room refuses to touch the problem at all. Zeus says no. The moment he says “not my problem,” I feel two things at once. One is disgust. The other is fascination. I can’t tell whether he’s dodging responsibility or designing a trap. He simply passed down the problem, which in this case is a verdict, into a “mouth that isn't his.” How clever of Zeus. He doesn’t actually remove himself from the equation. He merely creates enough distance between his actions and their consequences so that he can maintain plausible deniability. Not my problem. And yet the problem still moves forward, routed through other hands, but his remain clean while the story continues. Later, when suffering arrives, the story will have a culprit with a face, which is not his.

I tend to think being in a position of leadership demands a lot of decision-making and actions. But this one move from him is so very different from how the war had become a mortal burden because of old oaths. So ironic that gods wash their hands, but mortals took up the inevitable burden and carried it. Perhaps that’s the second weapon in this war, after the golden apple. War looks like blood, swords, and spears; that’s what is easy to see. What’s harder to see are these tiny courses of action that prepare violence long before anyone lifts a blade. In the Trojan War, this casual escape of responsibility created perfect conditions where violence became inevitable.

I remember how I first met the Trojan War in school. I memorized names, events, the story itself, to pass the exams. I never truly understood why the war starts, what makes conflict feel necessary to the people inside it, why a small insult or a public ranking has the power to spread and remain. Even now, when people fight, when the news carries wars into the room, the same question returns in a plain and helpless form. Why? Why should a conflict start at all? Why can’t people live and let live?

Perhaps the people who can say “not my problem” are often the ones with the power to actually solve the problem.

Refusal which leads to some other’s action is still an action. Refusal can keep hands clean while still making the thing happen. Sometimes it looks like avoidance, but the more I look at it, the more it feels like strategy. I can’t always tell whether it is refusal by avoidance or by design. The difference matters because those two don’t mean the same thing when someone is not strong enough and deflects out of fear, versus when someone is strong enough and deflects out of control. The story keeps asking a question:

How does one tell honest refusal from power hiding, when avoidance and strategy can have the same shape, separated only by who has strength and who does not?

Zeus outsourcing the mess into “a mouth that isn't his” pushes the responsibility into Paris’s mouth, into a small mortal life. The pattern repeats throughout our human history. Leaders speak through advisors, counselors, corporations, representatives. With each layer or step of separation, distance is added between the decision maker and the consequence bearer. The decision maker stays protected while the consequence bearer becomes identifiable, punishable, and blame-able. And it becomes clearer why fear gathers around decisions. In this case, not only the decision itself, but also the story people will tell about it later. The ruckus it would create if things go wrong. So hey, not me, it’s them. How easy it is to have a person-shaped explanation when we say we want justice. We want a name we can repeat and a face that can be made to stand in for the whole mess, because it’s too hard to stay angry at a system. To say “this person hurt me” is easier than to say “this thing hurt me.”

I wonder if Homer understood how god’s politics feel eerily familiar for human institutions thousands of years later. A perfect template for how power preserved itself by creating these layers of deniability or silence. Somebody else will bleed for it. Not always literal blood, at least not at first. Sometimes reputational blood comes first; the blood of who started it, who made the decision that triggered the chain of events. I don’t fully trust this move of Zeus, but I can see why stories do this. A human choice or mistake is easier to hate or punish than a god’s shrug.

Then another question opens: what does it mean to have the convenient option to opt out of consequences? Zeus can surely step back because, ultimately, he won’t be the one bleeding on the battlefield. The gods watch human suffering with the detached interest of spectators at some sporting event. We have not yet started the main narrative of the Iliad, but the gods have favorites, they place bets on their favorites, they occasionally interfere, but who’s the one bleeding? Actually bleeding? Gods are surely not invested in the way the mortals are.

I’d call this “watching distant suffering” today. It’s easy to watch wars, disasters, suffering one doesn’t experience directly but through screens. However, everybody has opinions, preferences; some might even donate or advocate, but there is still the ability to turn away when it becomes too much. “Not my problem” — that’s our privilege. Because one can close the app or change the channel, simply divert the attention elsewhere.

The relationship between power and responsibility in the Iliad feels deliberately imbalanced (at least presently). Influencing the events while not claiming ownership of outcomes. But the king of gods acting this way is dangerous. Because he is unbound by the consequences, with so much power to create potential harm. Why? When the greatest god steps back, the problem goes to smaller gods and mortals to fill the vacuum. The smaller ones don’t get to opt out or change the channel. That there is a trap, which is hard to escape once it has happened.

How neat Zeus’s move is! He was asked to pick a side in what could be called a child’s game. I can’t call him innocent, but I also can’t call him simply guilty. If there is one thing I’m taking back from this chunk of reading: Zeus has shown me a kind of power that doesn’t need to touch the knife. It only needs to decide whose hand will hold it, not the one who routed the problem. And then, later, when blood comes, everyone points to the hand holding the knife. Not the one who designed the situation or routed the problem.

If refusal can be an action, then how do we differentiate between honest refusal and power hiding?

The apple leaves the wedding hall, but it does not leave the story. It travels to a place where a verdict can be spoken without the speaker having the power to survive it. Soon the contest will stop being about being seen and become about what desire can buy when it is offered the wrong kind of authority.

Next up: I’ll be reading the Judgment of Paris. I’m curious to see what drew him to Aphrodite, and why he chose her over the other goddesses. I’ll share more of my thinking-on-paper thoughts as they come to me. Until then, take care.

Yours in thought,

Yana

Reading list:

Image credits:

@memorias_delpasado

Eris Greek Goddess by YeCuriosityShoppe

The Wedding of Peleus and Thetis by Peter Paul Rubens

The Judgement of Paris by Gustav Pope