Yana’s Oxford English Literature Personal Curriculum

A self-designed journey for reading, questioning, and writing

Quick Navigation

My Personal Curriculum — Jump right here for the detailed curriculum

Dear Reader,

For some time now, I have been working on building a personal curriculum for myself, which structures my English literature study and prepares me to apply for a detailed course/degree at Oxford.

What follows is my self-designed curriculum. It spans 6 modules, each with its own objectives, guiding questions, and assignments, culminating in a capstone project on R.F. Kuang’s Babel.

I am sharing it here in case it sparks ideas for others who are also trying to build their own pathways into English literature.

Full Curriculum: Scroll down to the section My Personal Curriculum

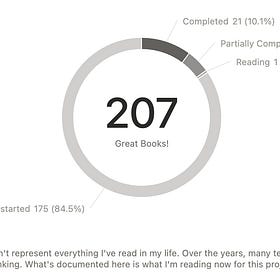

The Reading Project

I do not want to die before building a mind worth listening to. I’m reading and writing about demanding works across literature, philosophy, psychology, intellectual history, and the sciences of mind.

Why Personal Curriculum?

After much thought, I have come to a conclusion that there are countless ways to study literature (university courses, reading lists, YouTube). But I wanted something structured yet flexible for my needs and interests.

A framework that will allow me to:

Read chronologically, to see literature’s evolution over time.

Balance canonical texts with critical voices and present rewritings.

Get into writing: close readings, essays, and creative reflections.

Connect literature’s past with present questions of power, identity, and language. (My anchor interest)

My Personal Curriculum

Goals:

This personal curriculum is both a preparation and a commitment. It is my way of entering the long conversation of English literature before I step into Oxford’s halls. The works gathered here are not merely a checklist of canonical texts but a map of intellectual training: to read attentively, to think critically, and to write reflectively in my blog at Yana’s Reveries.

The project spans from the earliest English epic, Beowulf, through Chaucer, Shakespeare, Milton, the Romantics, the great Victorian novelists, the voices of Modernism, and into postcolonial and contemporary re-imaginings. It culminates in an extended essay on R. F. Kuang’s Babel – my chosen anchor text for the Oxford application. Each module also draws on critical voices to sharpen my own with a dialogue with criticism. The modules build incrementally toward this outcome, providing historical, thematic, and theoretical frameworks to read Babel in dialogue with the tradition it interrogates and inherits.

I aim for both breadth and depth: practicing close reading, testing guiding questions, exploring historical and theoretical contexts, and writing regularly in response. Each module includes objectives, predicted areas of research, guiding questions, and assignments that allow me to approach the texts as a student, not just a reader.

In undertaking this work, I prepare myself not only for an interview or application but for the intellectual life Oxford demands: one grounded in tradition, sharpened by criticism, and open to discovery.

Guiding Questions:

These questions mark the starting points of curiosity that will guide my reading, research, and reflective writing. They are not meant to be answered once and for all, but to be returned to across periods and texts, so that each work reshapes my perspective:

How has English literature evolved from its earliest oral and manuscript forms to the present, and what continuities persist across centuries?

In what ways is language itself represented as a tool of power – moral, political, aesthetic, or imperial – and how do writers resist or expose this power?

What does it mean for a work to belong to the “English canon”, and how have later writers affirmed, challenged, or reimagined it?

How do literary forms – epic, tragedy, lyric, novel, modernist fragmentation – both express and transform thought?

How do questions of gender, class, empire, and personal identity recur and mutate across centuries of writing?

How have institutions (church, monarchy, university, empire) shaped the production, preservation, and interpretation of literature?

How does my act of reading in the 21st century – with awareness of history, criticism, and my own positionality – alter my understanding of the canon?

How does R. F. Kuang’s Babel converse with this tradition – inheriting its forms, critiquing its assumptions, and imagining new futures?

Module I: Medieval & Early Foundations

Objective:

To explore the origins of English literature in its oral, allegorical, and courtly traditions; to understand how these works established early patterns of heroism, morality, and narrative authority; and to examine how questions of performance, gender, and community shaped medieval texts.

Texts to Read:

Beowulf (composed c. 700–1000, Heaney translation)

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (c. 1380–1400, modern translation by Keith Harrison or Simon Armitage)

Geoffrey Chaucer: The Canterbury Tales

General Prologue (c. 1387–1400)

Pardoner’s Tale (c. 1387–1400)

Wife of Bath’s Tale (c. 1387–1400)

Optional Readings (short selections):

J.R.R. Tolkien, Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics

Fred C. Robinson, The Tomb of Beowulf

Carolyn Dinshaw, Chaucer’s Sexual Poetics (excerpt)

Sarah Kay, Chivalry and Courtly Ideals in Sir Gawain

Predicted Areas of Research:

Oral tradition, manuscript culture, and the movement from performance to text.

Heroism, morality, and the role of Christianity in Beowulf, shaping narrative values.

Gender and authority in Chaucer, with special attention to competing voices in the Canterbury Tales.

Courtly ideals and the testing of virtue in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.

Guiding Questions:

What values of heroism and kingship does Beowulf uphold, and in what ways does the poem complicate them?

How does Sir Gawain negotiate the conflict between Christian virtue and chivalric ideals?

In the Canterbury Tales, how do the voices of the Pardoner and the Wife of Bath expose tensions of gender, authority, hypocrisy, and moral truth?

How does performance (oral, rhetorical, communal) shape meaning differently from written text?

What power does storytelling itself hold in these texts, and how might this anticipate later debates on language and power (Babel)?

Assignments (choose one):

Contextual Essay: Write an essay (~1,500 words) examining how Beowulf captures the transition from an oral storytelling culture to a written literary one. Discuss what is preserved or lost, when such stories move from collective performance to individual reading. Use examples from the poem and refer to at least one scholarly source on oral tradition or cultural memory.

Creative Reflection: Select 20-30 lines from Beowulf and rewrite them in modern English verse. Try to keep the original’s rhythm, sound, and sense of heroic tone. Then, write a short reflection (300–400 words) on your creative process. Comment on what changed when you translated the passage. Reflect on what was gained and lost in language, sound, and meaning when turning an Old English oral form into modern written poetry.

Analytical Essay: Write an essay (~1,500 words) analyzing how Sir Gawain and the Green Knight uses the idea of exchange of gifts, promises, and blows to test moral integrity. Explain how the exchange system works both literally (with objects) and symbolically (as moral testing). Analyze key scenes such as the beheading game and the exchanges with Lady Bertilak.

Dialogic Exercise: Write a short imagined dialogue (500-700 words) between Gawain and the Green Knight after the final blow. Let each character defend his view of truth, honor, and deception. Use language and tone appropriate to their personalities. Then, add a 200-300 word reflection explaining what this exchange reveals about the poem’s moral vision and how you interpreted their voices.

Comparative Essay: Write a ~1,500 word essay comparing The Wife of Bath’s Prologue and The Pardoner’s Tale. Examine how each speaker claims or undermines authority through storytelling. Analyze their tone, irony, and self-presentation. Conclude by considering whether Chaucer uses these figures to critique or uphold medieval ideas of morality and authority.

Reflective Journal: Write a reflective entry (700-900 words) on storytelling as pilgrimage in The Canterbury Tales. What does Chaucer suggest about truth, fiction, and moral purpose through the journey and frame narrative? Connect your insights to your own reading experience: how does this “pilgrimage of voices” shape the way you think about storytelling and interpretation?

Module II: Renaissance & Early Modern Drama

Objective:

To examine the flourishing of drama and epic in the Renaissance and early modern period, with special attention to questions of ambition, fate, theology, kingship, and gender. This module aims to explore how Shakespeare and Milton shaped enduring models of tragedy, comedy, and epic, and how their works continue to frame debates about morality and human agency.

Texts to Read:

William Shakespeare:

Hamlet (c. 1600–1601)

Macbeth (c. 1606)

King Lear (1606)

Othello (1604)

Twelfth Night (1601)

A Midsummer Night’s Dream (c. 1595–1596)

The Tempest (1611)

John Milton: Paradise Lost (1667; revised edition 1674)

Book I

Book II

Book IV

Book IX

Optional Readings (short selections):

A.C. Bradley, Shakespearean Tragedy (on Hamlet, Macbeth, King Lear)

Stephen Greenblatt, Renaissance Self-Fashioning (on identity and performance)

Lisa Jardine, Still Harping on Daughters (on women in Shakespeare)

C.S. Lewis, A Preface to Paradise Lost (on Milton’s epic form)

Stanley Fish, Surprised by Sin (on Milton’s rhetorical strategies)

Predicted Areas of Research:

The nature of tragedy: fate, ambition, and human frailty.

Kingship, legitimacy, and the politics of power in Shakespeare’s tragedies.

Gender, disguise, and comedy as social critique in Shakespeare’s comedies.

Theological and political stakes in Milton’s Paradise Lost: freedom, obedience, rebellion.

The figure of Satan as hero, villain, and rhetorician.

Language and rhetoric as tools of power and seduction.

Guiding Questions:

How do Shakespeare’s tragedies explore the fragility of human agency in the face of fate, ambition, or madness?

What kinds of authority – political, divine, personal – are tested and contested in these plays?

How do Shakespeare’s comedies use gender play, disguise, and performance to critique social norms?

What is the relationship between divine justice, free will, and rebellion in Paradise Lost?

Is Milton’s Satan a tragic hero, a moral lesson, or a rhetorical trickster?

How do Shakespeare and Milton stage the power – and danger – of rhetoric itself? (Babel)

Assignments (choose one):

Close Reading: Select a soliloquy from Hamlet or Macbeth and analyse its language of doubt, ambition, or self-reflection.

Comparative Essay: Tragic ambition and the fall: Macbeth and Milton’s Satan.

Research Essay: Comedy as critique: gender, disguise, and authority in Shakespeare’s comedies.

Performance Essay: Directorial notes on staging Hamlet’s “To be or not to be”, exploring interpretive choices.

Dialogic Essay: Write an imagined dialogue between Hamlet and Satan on free will, persuasion, and rebellion.

Module III: Romanticism & the Gothic Turn

Objective:

To investigate how the Romantic poets redefined nature, imagination, and the sublime, while also tracing the emergence of the Gothic as Romanticism’s shadow. This module considers how writers balance idealism with terror, innovation with tradition, and how questions of imagination, nature, and the supernatural shape literary form.

Texts to Read:

William Wordsworth:

Lines Written a Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey (1798)

Ode: Intimations of Immortality (1807)

Lucy Poems (1798–1801)

We Are Seven (1798)

Michael (1800)

Expostulation and Reply (1798)

The Tables Turned (1798)

Samuel Taylor Coleridge:

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1798; revised 1817)

The Nightingale (1798)

John Keats:

La Belle Dame sans Merci (1819; published 1820)

Bright Star (written 1819; published 1838)

Ode to Autumn (1819)

Ode on a Grecian Urn (1819)

Ode on Melancholy (1819)

Ode to a Nightingale (1819)

Mary Shelley: Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (1818; revised edition 1831)

Optional Readings (short selections):

Edmund Burke, On the Sublime and Beautiful (excerpts)

M.H. Abrams, The Mirror and the Lamp (on imagination)

Anne Mellor, Mary Shelley: Her Life, Her Fiction, Her Monsters

David Punter, The Literature of Terror

Predicted Areas of Research:

The sublime: terror, awe, and beauty in Romantic poetry.

The tension between Romantic idealism and Gothic darkness.

Nature as moral teacher versus nature as uncanny force.

The Gothic as critique of Enlightenment rationalism.

Women writers and the Gothic imagination.

Guiding Questions:

How does Wordsworth represent nature as a source of moral and spiritual renewal?

How does Coleridge intertwine imagination, guilt, and the supernatural in The Rime of the Ancient Mariner?

What is the “sublime” for Keats, and how is it embodied in his odes?

How does Frankenstein reflect Romantic ideals and simultaneously critique them?

What do Romantic and Gothic texts suggest about the limits of human knowledge, reason, and ambition?

How do Romantic/Gothic texts question Enlightenment rationalism – and how does this foreshadow Babel’s interrogation of empire and knowledge?

Assignments (choose one):

Close Reading: Analyse Tintern Abbey or The Rime of the Ancient Mariner with attention to their handling of nature and imagination.

Comparative Essay: Imagination and terror: Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner.

Research Essay: The Gothic as the dark twin of Romanticism: terror, reason, and the critique of Enlightenment thought.

Creative Exercise: Write a Romantic-style lyric on the sublime, drawn from a modern experience; reflect on Romantic form and context.

Critical Lens Essay: How does feminist criticism reshape our reading of Frankenstein?

Module IV: The Victorian Novel

Objective:

To investigate the rise of realism and the novel of manners, while also tracing how Victorian writers grappled with morality, gender, class, and social critique. This module examines how the legacy of Romanticism and Gothicism persists within a realist framework, and how the novel became the dominant form of the 19th century.

Texts to Read:

Jane Austen: Pride and Prejudice (1813)

Charlotte Brontë: Jane Eyre (1847)

Emily Brontë: Wuthering Heights (1847)

Charles Dickens: Great Expectations (1861)

George Eliot: Middlemarch (1871–1872)

Thomas Hardy: Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891)

Optional Readings (short selections):

Claudia Johnson, Jane Austen: Women, Politics, and the Novel

Sandra Gilbert & Susan Gubar, The Madwoman in the Attic (on Brontës)

Raymond Williams, The English Novel from Dickens to Hardy

George Levine, The Realistic Imagination

D.H. Lawrence, Study of Thomas Hardy

Predicted Areas of Research:

The marriage plot, morality, and women’s roles.

Realism versus Gothic inheritance in Victorian fiction.

Social class, morality, and industrial modernity.

Narrative voice, omniscience, and psychological interiority.

The tension between fate, choice, and social constraint.

Guiding Questions:

How do these novels interrogate morality, class, and women’s roles within Victorian society?

How do Brontë heroines subvert or embody Victorian ideals of femininity?

In what ways does Dickens dramatize moral failure and redemption through narrative form?

How does Eliot’s realism differ in scope and psychology from Dickens’s moral fables?

How does Hardy represent fate, tragedy, and the limits of agency in Tess of the d’Urbervilles?

What silences – colonial, class, gendered – underpin Victorian realism, and how do these absences foreshadow Babel’s critique of empire and language?

Assignments (choose one):

Close Reading: Analyse a passage of narrative voice from Middlemarch, with focus on the narrator’s role as moral guide.

Comparative Essay: The Gothic inheritance in Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights.

Research Essay: The marriage plot and female agency: Austen’s Pride and Prejudice and Hardy’s Tess of the d’Urbervilles.

Form Essay: Compare omniscience in Middlemarch with Dickens’s narrator in Great Expectations.

Creative Assignment: Rewrite a passage of Jane Eyre in Dickens’s style, then reflect critically on the transformation.

Critical Lens Essay: A Marxist vs moral reading of Great Expectations: what shifts in interpretation?

Module V: Modernism

Objective:

To understand the literary revolutions of the early 20th century, when writers broke from Victorian realism to experiment with fragmentation, myth, consciousness, and form. This module considers how Modernist literature responds to political upheaval, spiritual crisis, and the search for new meaning in a fractured world.

Texts to Read:

Joseph Conrad: Heart of Darkness (serialized 1899; published 1902)

James Joyce:

Dubliners (1914)

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916)

Virginia Woolf:

Mrs Dalloway (1925)

To the Lighthouse (1927)

A Room of One’s Own (1929)

T. S. Eliot:

The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock (1915)

The Waste Land (1922)

Murder in the Cathedral (1935)

Four Quartets (Burnt Norton 1936, Little Gidding 1942)

W. B. Yeats:

The Lake Isle of Innisfree (1890)

The Stolen Child (1886)

The Second Coming (1919)

Sailing to Byzantium (1927)

Among School Children (1928)

Leda and the Swan (1924)

Easter 1916 (1921)

The Circus Animals’ Desertion (1939)

Optional Readings (short selections):

Achebe, An Image of Africa (on Conrad)

Eliot, Tradition and the Individual Talent

Toril Moi, Sexual/Textual Politics (on Woolf)

Cleanth Brooks, The Waste Land: Critique of the Myth

Helen Vendler, Our Secret Discipline (on Yeats)

Predicted Areas of Research:

The crisis of meaning, faith, and tradition in early 20th century literature.

Stream of consciousness and the representation of time (Joyce, Woolf).

Myth, ritual, and symbolism in Eliot and Yeats.

Colonialism and the fractured moral landscape in Conrad.

Gender, identity, and voice in Woolf’s feminist essays and novels.

Guiding Questions:

How does Modernism respond to political, spiritual, and cultural crisis?

How do Woolf and Joyce reshape narrative time and consciousness?

How do Eliot and Yeats reinvent tradition through myth and ritual?

In what ways does Heart of Darkness anticipate Modernist fragmentation and expose colonial anxiety?

How does Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own reposition women within literary tradition?

How do Modernist debates about language and tradition anticipate postcolonial re-readings of canon and empire, including Babel?

Assignments (choose one):

Close Reading: Analyse the opening of Eliot’s The Waste Land with attention to fragmentation, allusion, and tone.

Comparative Essay: Time and consciousness in Woolf’s To the Lighthouse and Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.

Research Essay: Myth and ritual as modernist strategies: Eliot’s Four Quartets and Yeats’s Byzantium poems.

Critical Reception Essay: Achebe vs Conrad: The canon, colonialism, and moral blindness.

Creative Assignment: Rewrite a Woolf passage in Joyce’s style, then reflect on how form changes meaning.

Tradition Essay: Breaking and remaking tradition: Eliot’s Tradition and the Individual Talent vs Yeats’s Byzantium poems.

Module VI: Postcolonial & Contemporary Voices

Objective:

To explore how 20th and 21st century writers confront the legacies of empire, history, gender, and identity. This module examines how postcolonial and contemporary texts rewrite the English canon, reclaim suppressed voices, and use language itself as a site of power and resistance.

Texts to Read:

E. M. Forster: A Passage to India (1924)

Chinua Achebe: Things Fall Apart (1958)

Sylvia Plath: The Bell Jar (1963)

Toni Morrison: Beloved (1987)

R. F. Kuang: Babel, or the Necessity of Violence: An Arcane History of the Oxford Translators’ Revolution (2022)

Optional Readings (short selections):

Edward Said, Culture and Imperialism (on Forster/Achebe)

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Decolonising the Mind (on language & power)

Gayatri Spivak, Can the Subaltern Speak? (excerpt)

Cathy Caruth, Unclaimed Experience (on trauma)

Sandra Gilbert, The Plath Celebration: A Partial Dissent

Walter Benjamin, The Task of the Translator (as lens for Babel)

Predicted Areas of Research:

Postcolonial rewriting of the English literary tradition.

Language, translation, and the politics of representation.

Trauma, history, and memory in narrative.

Gender, voice, and agency in women’s writing.

Oxford and empire: the institution as both centre and symbol.

Guiding Questions:

How do Achebe and Forster differently represent empire, culture, and colonial encounter?

How does Morrison’s Beloved use narrative form to embody trauma and memory?

In what ways does The Bell Jar reflect mid-century crises of identity, gender, and autonomy?

How does Babel confront the English canon while positioning itself within it?

How is language itself weaponized or reclaimed in postcolonial and contemporary literature?

How does reading Babel retroactively reshape my understanding of the tradition – from medieval epic to modernism?

Assignments (choose one):

Close Reading: Analyse a chapter of Beloved that represents trauma and collective memory.

Comparative Essay: Empire and its afterlives: Achebe’s Things Fall Apart and Forster’s A Passage to India.

Research Essay: Language as violence and resistance: Kuang’s Babel in conversation with postcolonial fiction.

Theory Essay: Apply Said’s Culture and Imperialism to Forster and Achebe.

Translation Assignment: Translate or reframe a passage from any text in this module and critically reflect on the act of translation.

Comparative Tradition Essay: From Milton to Kuang: How does Babel rewrite the story of rebellion, language, and empire?

Capstone Project: The Oxford Essay on Babel

Objective:

To synthesise the entire curriculum into an extended essay (3,500–4,000 words) that will serve as both the intellectual culmination of this self-directed study and the foundation for my Oxford application. The capstone will position R. F. Kuang’s Babel (2022) as the anchor text, reading it in dialogue with the English literary tradition from Beowulf to Modernism and postcolonial literature.

Central Focus:

Babel is a novel about language, translation, and empire – but also about literature’s role in constructing and contesting cultural authority. The capstone essay will examine how Kuang confronts the English literary tradition, inheriting its forms and critiques while imagining new futures for literature.

Optional Readings (short selection to anchor essay):

Walter Benjamin, The Task of the Translator

Edward Said, Culture and Imperialism

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Decolonising the Mind

Gayatri Spivak, The Politics of Translation

C.S. Lewis, A Preface to Paradise Lost (on tradition/epic form, useful for Milton link)

Guiding Questions:

How does Babel inherit and interrogate the English literary canon?

In what ways does Kuang position translation as both violence and liberation?

How does Babel’s Oxford echo and subvert earlier depictions of power, learning, and authority in English literature?

How do the themes of ambition, morality, empire, and identity resonate across Paradise Lost, Romantic and Gothic texts, Victorian novels, Modernist experiments, and postcolonial rewriting – and culminate in Babel?

What does it mean for a 21st century novel to “belong” to the English tradition?

Essay Options (choose one):

Comparative Tradition Essay: From Paradise Lost to Babel: Language, Power, and the Fall of Empire. – Compare Milton’s Satan and Kuang’s translators as figures of ambition, rebellion, and moral ambiguity.

Canon & Counter-Canon Essay: Canon and Counter-Canon: Reading Babel Through English Literature. – Trace how Babel converses with Wordsworth, Shelley, Eliot, and Morrison – inheriting and resisting tradition at once.

Thematic Deep-Dive Essay: The Tower and the Text: Translation, Violence, and Resistance in Babel. – Focus on Babel itself, but bring in supporting comparisons from Chaucer, Shakespeare, Romantic poets, and postcolonial writers to show continuity and rupture.

Final Outcome:

A 3,500–4,000 word essay, structured as a critical dialogue between Babel, the canon it inherits, and the theoretical debates it ignites. This essay will serve as both the intellectual capstone of the curriculum and as a writing sample/talking point for the Oxford interview.

If you are reading this and thinking of your own path through literature, perhaps you will find here a model to adapt. A personal curriculum is exactly that: personal. But I think it will become rewarding when shared.

The Reading Project

I do not want to die before building a mind worth listening to. I’m reading and writing about demanding works across literature, philosophy, psychology, intellectual history, and the sciences of mind.

Yours in thought,

Yana

Coming from the perspective of an educational developer who works in post-secondary education, advising instructors on their own course designs, I feel confident in saying you've got a robust plan going here! What I noted in particular was the way in which you are reflecting the disciplinary discourse purposefully and through your syllabus design. I also liked how you've structured your assignments to 'choose one'. This is really strong, flexible design that gives the learner (you) choice depending on what you're inspired to create.

Do you mind if I include this post in a mini, informal analysis project I'm working on? I'm interested in studying posts about personal curricula to see what the common themes are, the process of development, and so on. All with the goal of sharing back what I learned here on Substack :)

Amazing ideas!