They told her no, she said watch me

#2 — The Greek Dispatches: Antigone by Sophocles

Slowly reading Greek literature, tragedies, and mythology as a long, lived thing by staying inside the events until they start giving me meaning.

An essay about moral courage in Antigone, a Greek tragedy by Sophocles.

Sometimes we don’t follow the order of events; we follow the order of grief.

Oedipus Rex was my first encounter with Greek tragedy, which kept me drawing back to the Theban plays, leading me to Antigone. Though Oedipus at Colonus comes next chronologically in the story, I chose Antigone partly to understand Sophocles’s writing process. He actually wrote Antigone first, followed by Oedipus the King, and then Oedipus at Colonus.

Written in or before 441 BCE, Antigone is a page in the book of all we’ve lost, and all we’re still fighting for. The play explores divine vs. human law, the weight women carried in that distant age, and what the limitations of authority can mean — then and today!

My essay on Oedipus Rex, a Greek tragedy by Sophocles about fate, free will, certainty, and prophecies.

For Those Who Haven’t Read It

Note: If you’ve already read the play or know the story, feel free to skip this section. For context on events before Antigone, read my Oedipus Rex essay.

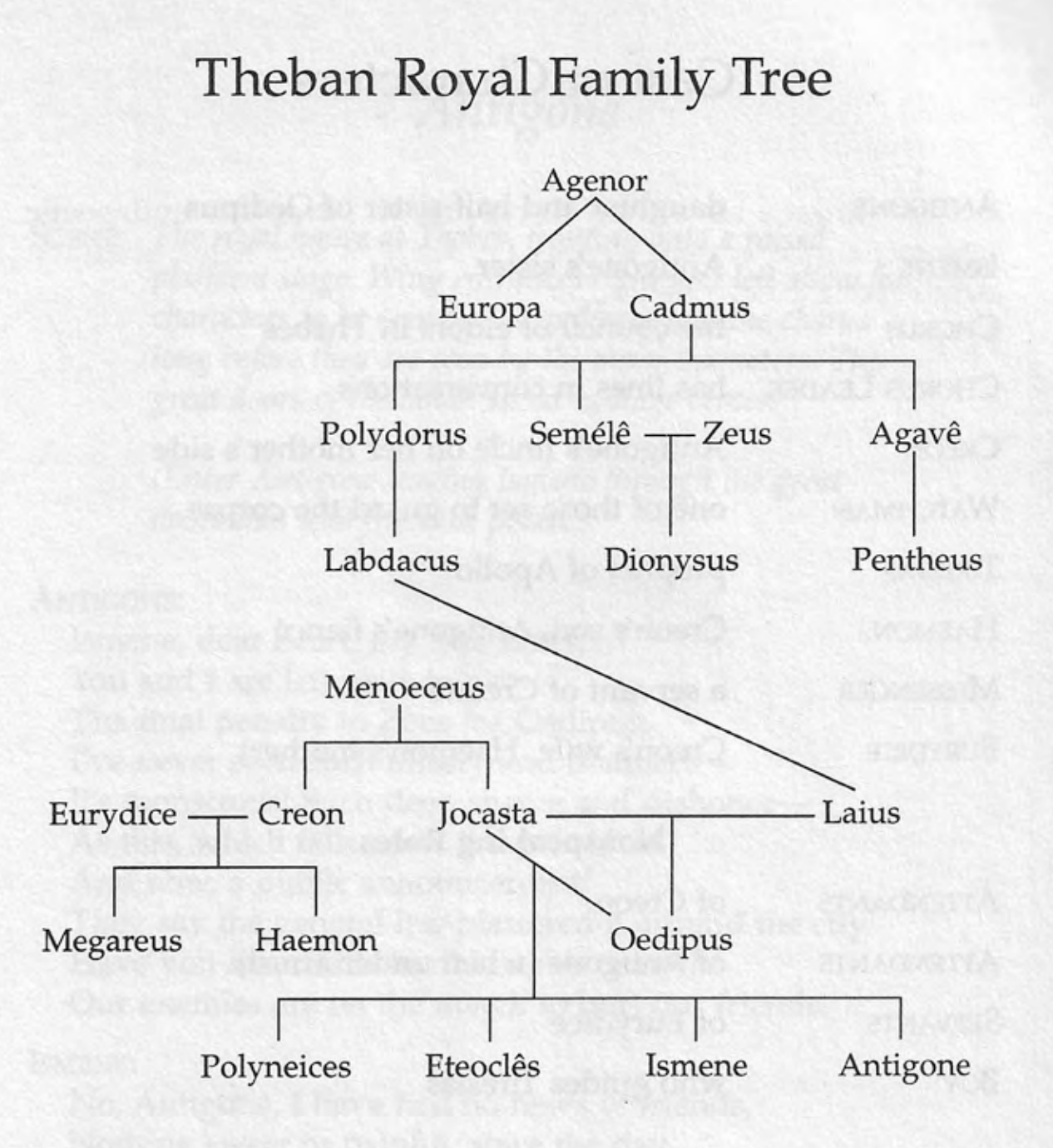

The two brothers (Oedipus’s sons Eteocles and Polyneices), fight because they had agreed to take turns ruling Thebes, but Eteocles refused to give up the throne when it was Polyneices’s turn. Polyneices then gathered an army from Argos to claim his rightful place, leading to a battle at the seven gates of Thebes where both brothers killed each other and their uncle Creon becomes king. He orders that Eteocles be buried with honor as a defender of the city, but Polyneices must be left unburied as a traitor. Their sister Antigone defies this order to honor divine law by burying Polyneices. When caught, she accepts her death sentence rather than back down. Her defiance triggers a tragic chain of events → Antigone’s death leads to the suicide of Haemon (Creon’s son and her fiance), which causes Eurydice (Creon’s wife) to take her own life. By the end, Creon understands his terrible mistake, but only after losing his entire family.

Female confrontation in a patriarchal world

In ancient Athens, women were considered legal minors throughout their lives, always under the guardianship of a male relative. They couldn’t own property independently, participate in politics, or even move freely in public spaces. Their primary value was in producing legitimate male heirs and maintaining the household.

Now imagine Antigone confronting THE KING! How bold! This becomes clearer when Creon, enraged at being challenged, says, “If she’s not punished for taking the upper hand, then I am not a man. She would be a man!” and later, “As long as I live, I will not be ruled by a woman.” What Antigone was unknowingly doing here was threatening Creon’s identity as a man in power.

I absolutely loved and admired the power of Antigone’s unflinching moral certainty. When Antigone was questioned if she’s not ashamed to have a mind apart from others, she does not back down. She believes divine law is higher than human law.

“I cannot side with hatred. My nature sides with love.”

“He has no right to keep me from my own.”

— Antigone, speaking of Creon’s order against burying her brother.

Compared to Ismene’s (her sister) submissive nature, Antigone has a clear sense of where she stands. Having such a strong will, especially in those times when men ruled, was astonishing!

“We are women and we do not fight with men. We’re subject to them because they’re stronger, and we must obey this order, even if it hurts us more.”

— Ismene

Reading these lines, I was slightly frustrated. Stronger in what way? I agree, physically stronger, by default. Setting aside gender, what makes someone right or just? What about mental strength? What about wisdom, values, nobility, and virtue?

Haemon: Younger but wiser than the older

I loved Haemon’s role in this tragedy. He stood right in the middle, caught between competing loyalties as Creon’s son and Antigone’s fiancé. And confronted his father’s rigidity with absolute wisdom!

Throughout the play, he makes powerful arguments about the nature of good leadership. He points out that the city actually supports Antigone, which reveals that Creon’s stance doesn’t represent the will of the people he claims to protect. Haemon tells his father that a good ruler should be willing to listen and adapt, and that wisdom comes not from rigidly holding one’s position, but from being open to other perspectives.

What I found interesting about Haemon’s argument compared to Antigone’s was that his came from a position of civic responsibility while hers appealed to divine law. His argument fell right between Antigone’s approach and Creon’s human tyranny.

Haemon showed that wisdom isn’t about age or power, but it’s about being willing to listen and change if proven wrong.

Divine vs. human law

At the heart of Antigone, the tragedy is about divine law vs. human law. Antigone stands very firmly on the side of divine law, insisting that the burial of the dead is a sacred duty that comes before any human order.

“No man could frighten me into taking on the god’s penalty for breaking such a law”

— Antigone

In all of the Theban tragedies, Tiresias (the priest) played such an important role. The blind prophet who serves as a bridge between the human and divine realms, eventually confirms Antigone’s position when he tells Creon: “The dead are no business of yours; not even the gods above own any part of them. You’ve committed violence against them.”

If Tiresias hadn’t appeared in the play, I wonder if Creon would have ever recognized his error. His stubbornness could have continued unchallenged, at least in his own mind.

“It is common knowledge, any human being can go wrong. But even when he does, a man may still succeed. He may have his share of luck and good advice but only if he’s willing to bend and find a cure for the trouble he’s caused. It’s only being stubborn proves you’re a fool.”

— Tiresias

The strength that we discussed earlier: I think true strength lies in being flexible enough to recognize and correct our errors.

Loyalty, authority, and Antigone’s relevance in current times

I was recently asked: is absolute loyalty to authority morally right?

Coincidentally, Antigone’s clear answer: NO. Sophocles shows us that moral authority doesn’t come from power or position, but from following principles, whether divine, as Antigone would have it, or the common good, as Haemon argues.

This tragedy feels so eerily modern because it’s screaming civil disobedience to state power. When laws violate our ethical principles or moral conscience, what should we do? Antigone’s tragedy is similar to → from civil rights protesters to whistleblowers who risk everything to expose wrongdoing. Like standing up for what we believe is right, even when it costs us everything, is what gives our lives meaning.

Moreover, Creon’s flaw is also very human: he can’t separate criticism from personal attack. When we hear something we don’t want to hear, we blame the messenger and take out our emotions on whoever delivered the news. How many of us respond to criticism by attacking the critic instead of considering whether the critique has merit?

Afterthoughts

I’m still thinking about moral certainty. I admire how brave and clear Antigone is, but I’m also worried about how absolute both she and Creon are in their beliefs. Being so certain about what’s right can be both heroic and destructive at the same time. It’s made me rethink what moral courage really means. Sometimes, sticking to what you believe is right, even when it costs you everything, shows the best of human character. But when you’re so certain that you won’t consider other options or change your mind, that certainty can make you blind to other truths. That’s why I appreciate Haemon and Tiresias → they’re willing to reconsider and adapt when needed, to bend and find a cure for the trouble one has caused. But I know the real world doesn’t always work that way.

I’m left wondering:

What if we all had the courage, like Antigone, to stand up against unfair authority?

Would that make our world better?

Or would things stay the same, and we’d be helpless, as we are now?

Does speaking up actually change anything?

What I’m Reading Next

The Iliad by Homer

The Odyssey by Homer

Yours in thought,

Yana

References for facts mentioned in this essay: